Owens Valley Indain Wars

Page 1 of 1

Owens Valley Indain Wars

Owens Valley Indain Wars

Location Maps

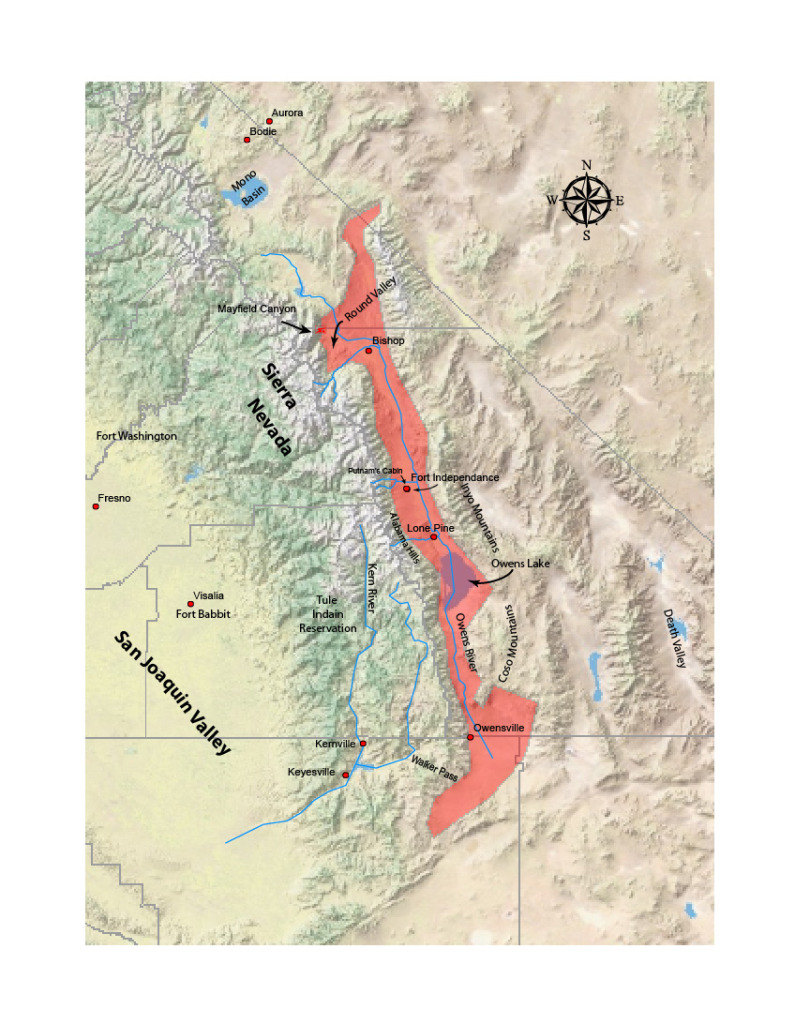

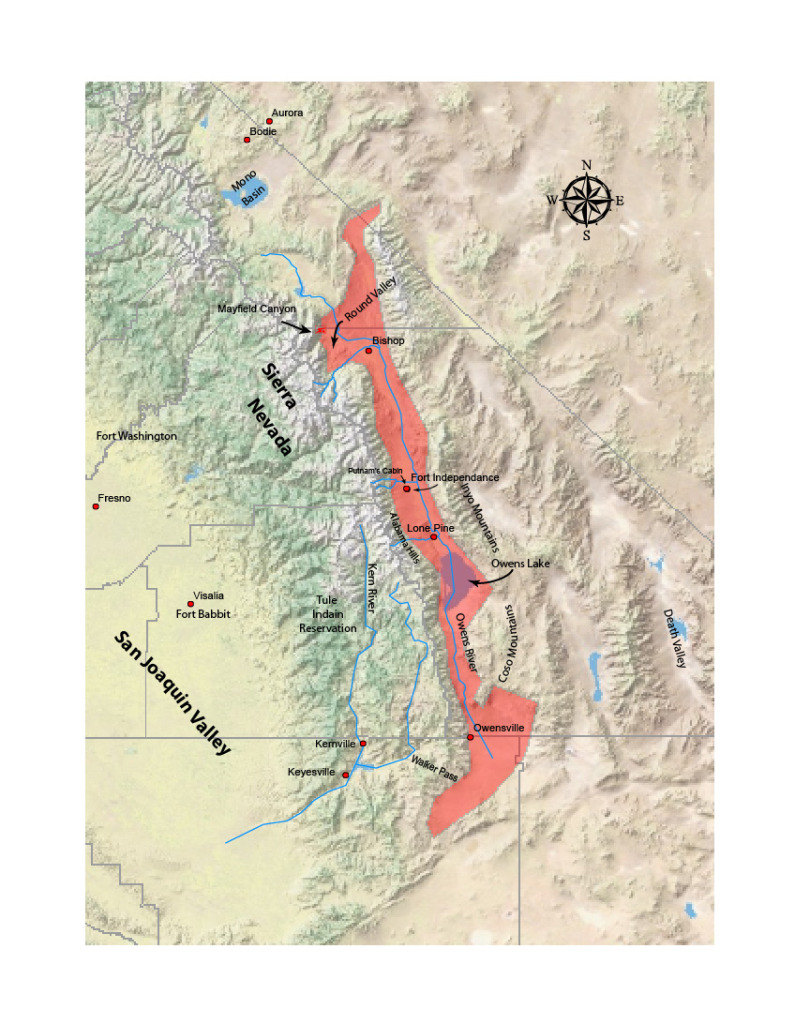

Red area denotes boundary of Owens Valley.

I made these maps to be references for the locations of events in the following article. I'm sorry the quality is so low, it was a bit of a rush job. If there is sufficient interest I'll go back and make a more professional quality image, however for the time being I think the above do a sufficient job conveying information. The below is from W. A. Chalfant's The Owens River Indian Wars part 1, from The Story of Inyo (1922) by way of the Nevada Observer.

Red area denotes boundary of Owens Valley.

I made these maps to be references for the locations of events in the following article. I'm sorry the quality is so low, it was a bit of a rush job. If there is sufficient interest I'll go back and make a more professional quality image, however for the time being I think the above do a sufficient job conveying information. The below is from W. A. Chalfant's The Owens River Indian Wars part 1, from The Story of Inyo (1922) by way of the Nevada Observer.

Last edited by Bryant on Wed May 16, 2012 3:01 am; edited 1 time in total

Bryant- Admin

- Posts : 1452

Join date : 2012-01-28

Age : 35

Location : John Day, Oregon

Re: Owens Valley Indain Wars

Re: Owens Valley Indain Wars

First, some background:

COMING OF THE STOCKMEN

The father and mother of McGee brothers, J. N. Summers, Mrs. Summers, Alney, John and Barton McGee, brothers, and A. T. McGee, a cousin, gathered a herd of beef cattle in Tulare County in the spring of 1861 and started for Monoville, Mono County, via Walker's Pass. Barton McGee's account relates that from Roberts' ranch on the south fork of Kern River to Adobe Meadows in Mono County, considerably more than 100 miles, not a white person or white settlement was seen. They estimated that there were 1,000 Indians then in Owens Valley, who were not friendly to the whites and considered that every one who came through their territory should pay tribute. Their demands on the McGee party were refused. No violence was offered, though efforts were made to stampede the cattle, until threats of death if there were further attempts in that direction put an end to such interference. The journey was finished without further molestation.

The first stockman to come this way to remain was Henry Vansickle, of Carson (then called Eagle) Valley, Nevada. A. Van Fleet came with him. W. S. Bailey drove his herds into Long Valley, just north of the Inyo line, about the same time.

Van Fleet was accompanied by men named Coverdale and Ethridge. The three went south as far as Lone Pine Creek, seeing no white men except a few scattered prospectors in the White Mountain foothills. Returning to the northern end of the valley, Van Fleet made camp at the river bend near the present site of Laws, and prepared for permanent residence. He put up a cabin of sod and stone, completing it in August, 1861 — the first white man's habitation in Owens Valley. He cut some wild hay that summer, the first harvest of any kind.

While Van Fleet was building, a rough stone cabin was begun by Putnam, at Independence, a stone's throw westerly from where the county jail now stands. The building was torn down in 1876. During the war period it was as much fortress as residence, and was used as house of refuge, home station and hospital. The neighborhood took the name of Putnam's, and was so known for some years. Once during the war, when the whites abandoned the valley, they prepared a surprise for any marauding natives who might undertake to destroy the cabin. A trench was dug around it and a quantity of blasting powder was poured into the trench, with a train leading to the wooden roof. The expectation was that one of the first acts of wreckage would be to burn the roof, and while the red men stood around enjoying the spectacle more or less of them would be blown into the happy hunting ground. But the close watch kept by the Indians defeated the plan. They carefully dug out the powder, and set a squaw at work with a stone mortar to reduce the large grains to suitable size for rifle use. While this was being done, a spark was struck in the mortar. The consequences were laconically explained by an Indian some years afterward; he told of gathering up the powder and putting some of it into the mortar, with the rest piled up close by, then "No mas (no more) ketchum squaw!"

Soon after Putnam put up his house, Fred Uhlmeyer and J. F. Wilson came from Visalia and "squatted" on land near Independence.

Samuel A. Bishop and his retinue started from Fort Tejon July 3, 1861, for the Owens River country, which had been examined by his scouts. Mrs. Bishop, the first white woman to tarry in the valley, came with her husband; in the party were also Mrs. Bishop's brother, named Sam Young, E. P. ("Stock") Robinson, Pat Gallagher and several Indian herders. They drove between 500 and 600 head of cattle and 50 horses. On August 22 they reached Bishop Creek, and established a camp at what Bishop named the San Francis Ranch, at a point where the stream leaves the higher sandy bench lands and gravel foothill slopes and enters the lower level of the valley, about three miles south of west of the present town of Bishop.

Pines growing near by were felled, and from them slabs were hewn for the construction of the first wooden structures, two small cabins.

While Bishop's residence in this valley was brief, as his name was given to the stream and later to the town we note some details of his career. Samuel Addison Bishop was born in Albemarle County, Virginia, September 2, 1825. He started for California April 15, 1849, and after an adventurous journey reached Los Angeles October 8th. We next hear of him as an officer in a war with the Mariposa Indians in 1851. By 1853, he was virtually in charge of the Indian reservation at Fort Tejon. That year he and General Beale, later prominent in Kern County affairs, formed a partnership in stockraising and land ownership. During the period he was the sole judge of what courts there were in the region, and appears to have filled his trust with credit. In 1854 he and Alex Godey, one of Fremont's scouts, contracted to furnish provisions for the troops at Fort Tejon. The government decided to build a military road from Fort Smith, Arkansas, to Fort Tejon, and Bishop and Beale took a contract for its construetion. While Beale began at the Fort Smith end, Bishop started to build easterly from Tejon. The partners were allowed the use of camels which the government had imported for desert work. The undertaking was full of adventures with which this record has no special concern.

Bishop's next venture was into this valley, after he and Beale had dissolved partnership. Following his stay in Inyo, he took a prominent part in affairs in Kern, and became one of that county's first Supervisors when its government was created in 1866. Two years later he and others secured a franchise for constructing a car line in San Jose, and that city was thereafter his home up to his death, June 3, 1893.

In the fall of 1861 J. S. Broder, Col. L. F. Cralley, Dan Wyman (hence Wyman Creek), Graves brothers and others came from Aurora to seek placer mines said to exist on the cast side of the White Mountains. They spent the winter on Cottonwood Creek. Early the following year Indians from farther eastward ordered them to leave, when Chief Joe Bowers interfered, saying it was his territory. He later warned the whites, however, that they had better go, as he might not be able to protect them though he wished to do so. They took his advice, after giving him such provisions as they did not need and caching their mining goods. After the first hostilities of the war had ended, the party went back, accompanied by T. F. A. Connelly. Joe helped them to find the cached goods, which had been raided. One item in the stock was a flask of quicksilver. A hole had been broken in the iron flask, and the metal spilled. In explaining the occurrence, Joe demonstrated by making motions of picking up something, then showing his empty fingers, with the remark: "Heap no ketchum." Joe was friendly to the whites throughout the Indian troubles; and as will later appear, one of the men he specially befriended had less of decency and justice in his makeup than did the aboriginal chief.

The brief tenancy of prospectors in "White Mountain District" in the fall of 1861 served as a basis for an attempted election fraud which attracted much attention in California legislative affairs in 1862 and 1863. That section, now in Inyo County, was then under Mono's jurisdiction. The latter county was joined in a legislative district with Tuolumne, for election of State Senator and Assemblyman.

"Big Springs Precinct" was established by Mono Supervisors, August 26, 1861, with its polling place at what is now known as Deep Springs. This was done by the Mono board on a request bearing one or two signatures. The election was held September 4th, so the precinct was created less than two weeks in advance.

The candidates for the State Senate from the district were Leander Quint, Union Democrat, and Joseph M. Cavis, Union; for the Assembly, B. K. Davis, Breckenridge Democrat, and Nelson M. Orr, Republican. Election returns as submitted by the County Clerk gave the vote as follows: For Senator: Cavis 372 in Mono, 1,664 in Tuolumne; total 2,036; Quint 741 in Mono, 1,467 in Tuolumne, total 2,208. For Assemblyman : Orr 1,728 in Tuolumne, 344 in Mono, total 2,072; Davis 1,563 in Tuolumne, 657 in Mono, total 2,220. On the face of the returns, therefore, Quint and Davis were elected.

Orr, of Tuolumne, was convinced that there was something wrong with the figures, so he came over to Mono and made a personal investigation. The returns of that county showed that Big Springs precinct had cast a total of 521 votes. McConnell, for Governor, had received 406 of these. Quint had been given 510, and Davis 298. Not a single Republican vote was noted, and another singular disclosure was that while a full State ticket was being elected no votes were returned for any office except Governor, Senator and Assemblyman. Orr visited Big Springs precinct, and was able to find only a handful of men in the region.

Orr and Cavis applied to the respective Houses of the Legislature to be seated in place of Davis and Quint. The Assembly Committee on Elections held a lengthy hearing, calling many witnesses from Mono County. Orr, petitioner, alleged that no election was held in the so-called Big Springs precinct, and produced evidence that there was virtually no population in the precinct. Davis' witnesses (none of whom were from the precinct) testified that they had sold goods to be taken to Big Springs to an amount indicating a large population, and that they believed there were at least 500 voters there. They also testified that one of Orr's witnesses had been paid $250 for his testimony. R. M. Wilson, County Clerk of Mono, when called on to produce the ballots and poll list, said he had mailed them to Sacramento, but singularly they failed to reach that city.

A witness testified that he saw the alleged poll list and election returns prepared in a cabin near Mono Lake; that they were written on torn fractional sheets of blue foolscap paper. Others were unable to identify more than two or three names on the alleged poll list, when it had been presented to the Supervisors, as being those of persons known to be in Mono County. A citizen who looked over the list was struck with the familiar appearance of some of the names, and finally ascertained that the list had been copied from the passenger list of the steamer on which he had come from Panama to San Francisco.

Notwithstanding the palpable fraud, a few in each House were found to support its beneficiaries. Orr was declared to have been elected, by vote of the Assembly February 13, 1862, forty-eight for Orr, four for Davis. The Senate, like the Assembly, had a Democratic majority in that session, but proved to be less ready to right the wrong; and it was not until March 28, 1863, well into the session of a year later, that Cavis was seated by a three-fourths Union Senate.

COMING OF THE STOCKMEN

The father and mother of McGee brothers, J. N. Summers, Mrs. Summers, Alney, John and Barton McGee, brothers, and A. T. McGee, a cousin, gathered a herd of beef cattle in Tulare County in the spring of 1861 and started for Monoville, Mono County, via Walker's Pass. Barton McGee's account relates that from Roberts' ranch on the south fork of Kern River to Adobe Meadows in Mono County, considerably more than 100 miles, not a white person or white settlement was seen. They estimated that there were 1,000 Indians then in Owens Valley, who were not friendly to the whites and considered that every one who came through their territory should pay tribute. Their demands on the McGee party were refused. No violence was offered, though efforts were made to stampede the cattle, until threats of death if there were further attempts in that direction put an end to such interference. The journey was finished without further molestation.

The first stockman to come this way to remain was Henry Vansickle, of Carson (then called Eagle) Valley, Nevada. A. Van Fleet came with him. W. S. Bailey drove his herds into Long Valley, just north of the Inyo line, about the same time.

Van Fleet was accompanied by men named Coverdale and Ethridge. The three went south as far as Lone Pine Creek, seeing no white men except a few scattered prospectors in the White Mountain foothills. Returning to the northern end of the valley, Van Fleet made camp at the river bend near the present site of Laws, and prepared for permanent residence. He put up a cabin of sod and stone, completing it in August, 1861 — the first white man's habitation in Owens Valley. He cut some wild hay that summer, the first harvest of any kind.

While Van Fleet was building, a rough stone cabin was begun by Putnam, at Independence, a stone's throw westerly from where the county jail now stands. The building was torn down in 1876. During the war period it was as much fortress as residence, and was used as house of refuge, home station and hospital. The neighborhood took the name of Putnam's, and was so known for some years. Once during the war, when the whites abandoned the valley, they prepared a surprise for any marauding natives who might undertake to destroy the cabin. A trench was dug around it and a quantity of blasting powder was poured into the trench, with a train leading to the wooden roof. The expectation was that one of the first acts of wreckage would be to burn the roof, and while the red men stood around enjoying the spectacle more or less of them would be blown into the happy hunting ground. But the close watch kept by the Indians defeated the plan. They carefully dug out the powder, and set a squaw at work with a stone mortar to reduce the large grains to suitable size for rifle use. While this was being done, a spark was struck in the mortar. The consequences were laconically explained by an Indian some years afterward; he told of gathering up the powder and putting some of it into the mortar, with the rest piled up close by, then "No mas (no more) ketchum squaw!"

Soon after Putnam put up his house, Fred Uhlmeyer and J. F. Wilson came from Visalia and "squatted" on land near Independence.

Samuel A. Bishop and his retinue started from Fort Tejon July 3, 1861, for the Owens River country, which had been examined by his scouts. Mrs. Bishop, the first white woman to tarry in the valley, came with her husband; in the party were also Mrs. Bishop's brother, named Sam Young, E. P. ("Stock") Robinson, Pat Gallagher and several Indian herders. They drove between 500 and 600 head of cattle and 50 horses. On August 22 they reached Bishop Creek, and established a camp at what Bishop named the San Francis Ranch, at a point where the stream leaves the higher sandy bench lands and gravel foothill slopes and enters the lower level of the valley, about three miles south of west of the present town of Bishop.

Pines growing near by were felled, and from them slabs were hewn for the construction of the first wooden structures, two small cabins.

While Bishop's residence in this valley was brief, as his name was given to the stream and later to the town we note some details of his career. Samuel Addison Bishop was born in Albemarle County, Virginia, September 2, 1825. He started for California April 15, 1849, and after an adventurous journey reached Los Angeles October 8th. We next hear of him as an officer in a war with the Mariposa Indians in 1851. By 1853, he was virtually in charge of the Indian reservation at Fort Tejon. That year he and General Beale, later prominent in Kern County affairs, formed a partnership in stockraising and land ownership. During the period he was the sole judge of what courts there were in the region, and appears to have filled his trust with credit. In 1854 he and Alex Godey, one of Fremont's scouts, contracted to furnish provisions for the troops at Fort Tejon. The government decided to build a military road from Fort Smith, Arkansas, to Fort Tejon, and Bishop and Beale took a contract for its construetion. While Beale began at the Fort Smith end, Bishop started to build easterly from Tejon. The partners were allowed the use of camels which the government had imported for desert work. The undertaking was full of adventures with which this record has no special concern.

Bishop's next venture was into this valley, after he and Beale had dissolved partnership. Following his stay in Inyo, he took a prominent part in affairs in Kern, and became one of that county's first Supervisors when its government was created in 1866. Two years later he and others secured a franchise for constructing a car line in San Jose, and that city was thereafter his home up to his death, June 3, 1893.

In the fall of 1861 J. S. Broder, Col. L. F. Cralley, Dan Wyman (hence Wyman Creek), Graves brothers and others came from Aurora to seek placer mines said to exist on the cast side of the White Mountains. They spent the winter on Cottonwood Creek. Early the following year Indians from farther eastward ordered them to leave, when Chief Joe Bowers interfered, saying it was his territory. He later warned the whites, however, that they had better go, as he might not be able to protect them though he wished to do so. They took his advice, after giving him such provisions as they did not need and caching their mining goods. After the first hostilities of the war had ended, the party went back, accompanied by T. F. A. Connelly. Joe helped them to find the cached goods, which had been raided. One item in the stock was a flask of quicksilver. A hole had been broken in the iron flask, and the metal spilled. In explaining the occurrence, Joe demonstrated by making motions of picking up something, then showing his empty fingers, with the remark: "Heap no ketchum." Joe was friendly to the whites throughout the Indian troubles; and as will later appear, one of the men he specially befriended had less of decency and justice in his makeup than did the aboriginal chief.

The brief tenancy of prospectors in "White Mountain District" in the fall of 1861 served as a basis for an attempted election fraud which attracted much attention in California legislative affairs in 1862 and 1863. That section, now in Inyo County, was then under Mono's jurisdiction. The latter county was joined in a legislative district with Tuolumne, for election of State Senator and Assemblyman.

"Big Springs Precinct" was established by Mono Supervisors, August 26, 1861, with its polling place at what is now known as Deep Springs. This was done by the Mono board on a request bearing one or two signatures. The election was held September 4th, so the precinct was created less than two weeks in advance.

The candidates for the State Senate from the district were Leander Quint, Union Democrat, and Joseph M. Cavis, Union; for the Assembly, B. K. Davis, Breckenridge Democrat, and Nelson M. Orr, Republican. Election returns as submitted by the County Clerk gave the vote as follows: For Senator: Cavis 372 in Mono, 1,664 in Tuolumne; total 2,036; Quint 741 in Mono, 1,467 in Tuolumne, total 2,208. For Assemblyman : Orr 1,728 in Tuolumne, 344 in Mono, total 2,072; Davis 1,563 in Tuolumne, 657 in Mono, total 2,220. On the face of the returns, therefore, Quint and Davis were elected.

Orr, of Tuolumne, was convinced that there was something wrong with the figures, so he came over to Mono and made a personal investigation. The returns of that county showed that Big Springs precinct had cast a total of 521 votes. McConnell, for Governor, had received 406 of these. Quint had been given 510, and Davis 298. Not a single Republican vote was noted, and another singular disclosure was that while a full State ticket was being elected no votes were returned for any office except Governor, Senator and Assemblyman. Orr visited Big Springs precinct, and was able to find only a handful of men in the region.

Orr and Cavis applied to the respective Houses of the Legislature to be seated in place of Davis and Quint. The Assembly Committee on Elections held a lengthy hearing, calling many witnesses from Mono County. Orr, petitioner, alleged that no election was held in the so-called Big Springs precinct, and produced evidence that there was virtually no population in the precinct. Davis' witnesses (none of whom were from the precinct) testified that they had sold goods to be taken to Big Springs to an amount indicating a large population, and that they believed there were at least 500 voters there. They also testified that one of Orr's witnesses had been paid $250 for his testimony. R. M. Wilson, County Clerk of Mono, when called on to produce the ballots and poll list, said he had mailed them to Sacramento, but singularly they failed to reach that city.

A witness testified that he saw the alleged poll list and election returns prepared in a cabin near Mono Lake; that they were written on torn fractional sheets of blue foolscap paper. Others were unable to identify more than two or three names on the alleged poll list, when it had been presented to the Supervisors, as being those of persons known to be in Mono County. A citizen who looked over the list was struck with the familiar appearance of some of the names, and finally ascertained that the list had been copied from the passenger list of the steamer on which he had come from Panama to San Francisco.

Notwithstanding the palpable fraud, a few in each House were found to support its beneficiaries. Orr was declared to have been elected, by vote of the Assembly February 13, 1862, forty-eight for Orr, four for Davis. The Senate, like the Assembly, had a Democratic majority in that session, but proved to be less ready to right the wrong; and it was not until March 28, 1863, well into the session of a year later, that Cavis was seated by a three-fourths Union Senate.

Bryant- Admin

- Posts : 1452

Join date : 2012-01-28

Age : 35

Location : John Day, Oregon

Re: Owens Valley Indain Wars

Re: Owens Valley Indain Wars

BEGINNING OF INDIAN WAR

As the winter of 1861-62 approached, some of the cattlemen who had driven into Owens Valley saw no reason for leaving its abundant grazing. As late as the first week in November Barton and Alney McGee got together a drove of 1,500 head of cattle, and came this way. While they were at Lone Pine, on November 12th, snow fell to a depth of four inches. They went on to George's Creek, then concluded to winter in the valley. Barton McGee reported that there were then settlers on Little Pine Creek (Independence), Bishop Creek and in Round Valley. He went to Aurora for supplies, where he found eight feet of snow. Returning with provender, the party went to Lone Pine and put up a cabin. Fine weather favored them until Christmas Eve, when there came the real beginning of probably the hardest winter that white men ever saw in Inyo. McGee noted that there was not a day of the next fifty-four without a downpour of either rain or snow; "not continuous," he wrote, "but at no time did it quit for a whole day, snowing to a depth of two feet or more and then raining it off. The whole country was soaked through and all the hills were deeply covered. All the streams became almost impassable, while the river was from one-fourth to one mile in width, about half ice and half water, and sweeping on to the lake, paying no respect to the crooks and curves of the old channel in its course to the lake, which it raised twelve feet." These reports of severe weather in Inyo are corroborated by official records for other parts of California, for during that January the rainfall at Sacramento was over fifteen inches. A book published two years later refers to the floods of that winter as "the most overwhelming and disastrous that have visited this State since its occupation by Americans." The first flood submerged the Sacramento Valley about December 10th, the water rising higher than in either of the memorable floods of 1851 and 1852. For six weeks thereafter an unusual amount of rain descended. On the 24th of January the second flood attained its greatest height, and the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys were transformed into a broad inland sea stretching from the foothills of the Sierra to the Coast Range, and somewhat similar in extent and shape to Lake Michigan. In that same month of January, a rain of three days' duration fell on the accumulated snow around Aurora, many of the adobe and stone buildings of the camp fell, and loss of life was occasioned by a flood in Bodie creek. The McGee account indicates that Owens Valley shared fully in the great downpour.

The few white men in the valley had nothing on which to subsist except beef, and much of the time they were without salt to make their monotonous fare more palatable. What must have been the plight of the Indians? Life was a hard struggle for them at the best; and under the conditions of that severe winter the herds of the whites offered the only means of preventing starvation. Besides, the Piute held that the white men were intruders. That the natives began to gather food from the ranges was only what might have been expected; it was what most white men would have done under such circumstances. The whites submitted to the loss of many animals before beginning retaliation.

The first act of revenge by the white men occurred when Al Thompson, a herder in Vansickle's employ, saw an Indian driving away an animal and promptly shot him. This occurred not far southeast of Bishop. A man named Crossen, better known as Yank, was then captured and killed by the Indians. He had come from Aurora and had stayed for a few days with Van Fleet. He crossed the river to the west side and was taken not far from where Thompson had done his killing. All that was ever seen of him again was part of his scalp, found at Big Pine.

It appears to be true, however, that scalping was not a usual practice of the Owens Valley Indians. Instances of that kind were very few. During the Indian war, a collection of a dozen scalps of white men were found in a cave near Haiwai (now Haiwee). The supposition was that they were evidence of a massacre by some other tribe.

The principal Indian settlement of the northern part of the valley was on Bishop Creek, within a short distance of Bishop's camp. Indians from all parts of the valley, and beyond, gathered there in the fall of 1861 and held a big fandango. Among those who were mixing war medicine were the usual sorcerers, who claimed that their magic would make the white men's guns so they could not be fired. The anxious stockmen kept their weakness concealed as well as they could, until reinforcements happened to arrive. A storm had wet the guns in camp, and to insure their reliability when needed they were taken outside and fired. This, disclosing to the tribesmen that the sorcerers' guarantees were not wholly dependable, helped to prevent the threatened assault, and the gathered Indians moved away.

The situation caused great alarm among the scattered settlers, and they gladly agreed to a pow-pow with the Indian chieftains. This conference was held at the San Francis ranch on the last day of January, 1862. Chief George defined the Indian view by marking two lines on the ground to show that the score was then even, referring to the Indian killed by Thompson, and the killing of Crossen. A treaty was drawn up and signed, as follows :

"We the undersigned, citizens of Owens Valley, with Indian chiefs representing the different tribes and rancherias of said valley, having met together at San Francis ranch, and after talking over all past grievances, have agreed to let what is past be buried in oblivion; and as evidence of all things that have transpired having been amicably settled between both Indians and whites, each one of the chiefs and whites present have voluntarily signed their names to this instrument of writing.

"And it is further agreed that the Indians are not to be molested in their daily avocations by which they gain an honest living.

"And it is further agreed upon the part of the Indians that they are not to molest the property of the whites, nor to drive off or kill cattle that are running in the valley, and for both parties to live in peace and strive to promote amicably the general interests of both whites and Indians.

"Given under our hands at San Francis ranch this 31st day of January, 1862."

Signed for the Indians by Chief George, Chief Dick and Little Chief Dick, each of whom made his mark; for the whites by Samuel A. Bishop, L. J. Cralley, A. Van Fleet, S. E. Graves, W. A. Greenly, T. Everlett, John Welch, J. S. Howell, Daniel Wyman, A. Thomson and E. P. Robinson.

One of the chiefs missing from the conference was Joaquin Jim, leader of the tribe in southern Mono, which then included the valley as far south as Big Pine Creek. It was probably Joaquin Jim's braves who began renewed depredations. At any rate, the treaty proved to be merely a passing incident. Within two months war was on in earnest.

During February Jesse Summers came from Aurora for beef for that market. He gathered a few in the southern end of the valley and went back to Aurora, leaving Bart and Alney McGee to drive the band. They got as far as Big Pine Creek, where Jim's camp happened to be at the time. Jim and a few of his men visited the McGee camp, and acted so unfriendly that the brothers concluded to move. Alney went to get the horses, and Jim demanded something to eat. Bart poured him a cup of coffee, which he threw, cup and all, into the fire. McGee jumped toward the guns, which the Indians had set to one side. McGee took the precaution to discharge the weapons, then told Jim to take them and go, which he did. The brothers moved on and spent the night safely though uncomfortably in a wet meadow, with their horses close at hand. Alney went on the next day with Summers, whom he met at Van Fleet's. Bart went to the San Francis ranch. The next day he rode back to Putnam's and reported that the northern settlers wanted help. On his way down the speed of his horse got him safely past a band of Indians at Fish Springs, untouched by the many shots they fired at him.

Fifteen men came with McGee from Putnam's to help to move the cattle from Bishop Creek. The night they reached the San Francis ranch the Piutes provided a striking exhibition of fireworks, running about and waving burning pitchpine torches secured to long poles. The Indians surrounded the cabin and sent in a delegation. Though they claimed to be friendly, they held a war dance around the building, and told the whites that the Piutes had charmed lives and could spit out the bullets that might enter their bodies. The night passed without violence.

The next morning the drive of stock began, reaching what is now Keough's Hot Springs the first night. Though pickets were put out, Indians succeeded in driving off 200 or more head of cattle. The next morning three of the men went after the stock, and were met by a line of forty or fifty Indians who ordered them back — an order with which they could do nothing but comply. Indians hovered about the flanks of the drive down the valley, but did not molest it further.

A few days later Barton and John McGee, Taylor McGee, Allen Van Fleet, James Harness, Tom Hubbard, Tom Passmore, Pete Wilson and Charley Tyler ("Nigger Charley") were near Putnam's when they saw four Indians going toward the cattle. Bart and Taylor McGee, Van Fleet, Harness and Tyler went out to where they were. The Indians when interrogated said they were going after their horses. They were told they could go on, but must leave their weapons until they came back. This they refused to do. The controversy continued for some time. One account is that Van Fleet made the first threatening move by leveling his gun at an Indian ; his own story, and that of other whites, was that the Indian first pointed an arrow at him. Whatever the facts of this, Van Fleet turned his body and got the first wound, an arrow in his side, where its obsidian head remained until his death fifty years later. Harness was also wounded before the whites shot. In the melee which ensued all the Indians, one of whom was Chief Shondow, were slain. Hubbard was shot through the arm with an arrow.

It is fully possible that the whites were to blame in this affair. An account reaching Aurora held them responsible, and Barton McGee, in writing of it, said: "This occurrence created a little trouble in our ranks, some thinking we were not justified in firing on them and others saying we did exactly right. Be that as it may, it was done." This does not well accord with the narration of the fight as above printed on the statements of McGee and Van Fleet.

A few more than forty white men were gathered at Putnam's, and they began to strengthen their fortification. Rocks, old wagons, boxes and other materials were used to pile up a barricade. Charles Anderson was elected captain, and a constant guard was maintained while the company remained there. Sheriff Scott, of Mono, was among the men, and in a letter said : "The Indians appear warlike here, and we expect a battle before many days—possibly tonight. There are forty-two of us, armed with rifles, shotguns and six-shooters. We have fortified ourselves the best we could with wagons, oxbows, yokes, rawhides, etc. I can escape easily, but to do so would be to weaken the force in the fort, and so enable the redskins to wipe out those who would be obliged to remain."

A band of natives had gone to Van Fleet's cabin on the river, previous to this gathering at Putnam's, and had demanded admission. After some parley he gave them provisions. They set out toward Benton, then known as Hot Springs, where a prospector named E. S. Taylor lived alone. Taylor's cabin was attacked and riddled with bullets and he was killed, but not until ten of his assailants had paid with their lives. Van Fleet was the only authority for this statement, except that others wrote of passing and seeing the bullet-riddled building. A report taken to Aurora by Albert Jeffway, an express rider who had been in Owens Valley, told of the death of another Taylor, near Putnam's. Taylor, he said, was hotheaded, and got into a row during which he killed two or three Indians. The Piutes set fire to his cabin, and as he came from it they shot him. It is at least possible that this was a mistaken version of the Benton affair.

Two men known as Vance and Shorty were still in the upper end of the valley, or may have gone there from Putnam's, to gather up what stock they could. Seeing Indians after their animals, they went to investigate, were fired on, and killed two natives.

Whatever of division there may have been in the Putnam camp over the killing of Shondow, there was no dissent when it was proposed to strike a blow that would discourage raids on the cattle. Preparations for a campaign were made, and twenty-three men, led by Anderson, left Putnam's after dusk masked their movements. Cralley was chosen lieutenant. Scott Broder, the Me-Gees, Tyler, Harness and Shea were among those in the column, which went that night to the sod cabin of Ault and Sadler, not far from the Alabama hills

As soon as the east began to gray, three men were left with the horses at the cabin and the others set out in two equal squads. Anderson's detachment went to where the light of campfires could be seen over the Alabama hills ; the others went up the stream. The sun was just rising as Anderson came up to where the Indians were breakfasting. Firing commenced at once, a number of Indians being killed at the first volley. They ran to shelter in the rocks, "and a good shelter it was," wrote Bart McGee, "cavities where they were out of sight in less than thirty seconds. We could not follow them in, so we did the best we could from the outside, shooting into the mouths of their dens, while the Indians threw arrows among us in showers. It seemed the air was full of arrows all the time. They did not have any guns or they would have made it a hard fight for us. We fought there for about an hour before the other boys, hearing our firing and coming across the rough hill, could reach us. We fought until about 1 o'clock, hitting some 30 or 40 of them, destroying about a ton of dried meat and some of their camp outfits." The white casualties included another arrow hole in Hubbard's arm, a wound in Harness' forehead made by an arrow which shattered against the skull without penetrating, and an arrow wound in Scott Broder's shoulder. The last mentioned injury was so troublesome that the citizens withdrew to the fort, leaving the natives in their stronghold. While McGee mentions that 30 or 40 Indians were hit, and another account said that Negro Charley Tyler himself shot four Indians, a report sent to Los Angeles gave the total Indian strength in the fight as 40 and said that their dead numbered eleven.

As the winter of 1861-62 approached, some of the cattlemen who had driven into Owens Valley saw no reason for leaving its abundant grazing. As late as the first week in November Barton and Alney McGee got together a drove of 1,500 head of cattle, and came this way. While they were at Lone Pine, on November 12th, snow fell to a depth of four inches. They went on to George's Creek, then concluded to winter in the valley. Barton McGee reported that there were then settlers on Little Pine Creek (Independence), Bishop Creek and in Round Valley. He went to Aurora for supplies, where he found eight feet of snow. Returning with provender, the party went to Lone Pine and put up a cabin. Fine weather favored them until Christmas Eve, when there came the real beginning of probably the hardest winter that white men ever saw in Inyo. McGee noted that there was not a day of the next fifty-four without a downpour of either rain or snow; "not continuous," he wrote, "but at no time did it quit for a whole day, snowing to a depth of two feet or more and then raining it off. The whole country was soaked through and all the hills were deeply covered. All the streams became almost impassable, while the river was from one-fourth to one mile in width, about half ice and half water, and sweeping on to the lake, paying no respect to the crooks and curves of the old channel in its course to the lake, which it raised twelve feet." These reports of severe weather in Inyo are corroborated by official records for other parts of California, for during that January the rainfall at Sacramento was over fifteen inches. A book published two years later refers to the floods of that winter as "the most overwhelming and disastrous that have visited this State since its occupation by Americans." The first flood submerged the Sacramento Valley about December 10th, the water rising higher than in either of the memorable floods of 1851 and 1852. For six weeks thereafter an unusual amount of rain descended. On the 24th of January the second flood attained its greatest height, and the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys were transformed into a broad inland sea stretching from the foothills of the Sierra to the Coast Range, and somewhat similar in extent and shape to Lake Michigan. In that same month of January, a rain of three days' duration fell on the accumulated snow around Aurora, many of the adobe and stone buildings of the camp fell, and loss of life was occasioned by a flood in Bodie creek. The McGee account indicates that Owens Valley shared fully in the great downpour.

The few white men in the valley had nothing on which to subsist except beef, and much of the time they were without salt to make their monotonous fare more palatable. What must have been the plight of the Indians? Life was a hard struggle for them at the best; and under the conditions of that severe winter the herds of the whites offered the only means of preventing starvation. Besides, the Piute held that the white men were intruders. That the natives began to gather food from the ranges was only what might have been expected; it was what most white men would have done under such circumstances. The whites submitted to the loss of many animals before beginning retaliation.

The first act of revenge by the white men occurred when Al Thompson, a herder in Vansickle's employ, saw an Indian driving away an animal and promptly shot him. This occurred not far southeast of Bishop. A man named Crossen, better known as Yank, was then captured and killed by the Indians. He had come from Aurora and had stayed for a few days with Van Fleet. He crossed the river to the west side and was taken not far from where Thompson had done his killing. All that was ever seen of him again was part of his scalp, found at Big Pine.

It appears to be true, however, that scalping was not a usual practice of the Owens Valley Indians. Instances of that kind were very few. During the Indian war, a collection of a dozen scalps of white men were found in a cave near Haiwai (now Haiwee). The supposition was that they were evidence of a massacre by some other tribe.

The principal Indian settlement of the northern part of the valley was on Bishop Creek, within a short distance of Bishop's camp. Indians from all parts of the valley, and beyond, gathered there in the fall of 1861 and held a big fandango. Among those who were mixing war medicine were the usual sorcerers, who claimed that their magic would make the white men's guns so they could not be fired. The anxious stockmen kept their weakness concealed as well as they could, until reinforcements happened to arrive. A storm had wet the guns in camp, and to insure their reliability when needed they were taken outside and fired. This, disclosing to the tribesmen that the sorcerers' guarantees were not wholly dependable, helped to prevent the threatened assault, and the gathered Indians moved away.

The situation caused great alarm among the scattered settlers, and they gladly agreed to a pow-pow with the Indian chieftains. This conference was held at the San Francis ranch on the last day of January, 1862. Chief George defined the Indian view by marking two lines on the ground to show that the score was then even, referring to the Indian killed by Thompson, and the killing of Crossen. A treaty was drawn up and signed, as follows :

"We the undersigned, citizens of Owens Valley, with Indian chiefs representing the different tribes and rancherias of said valley, having met together at San Francis ranch, and after talking over all past grievances, have agreed to let what is past be buried in oblivion; and as evidence of all things that have transpired having been amicably settled between both Indians and whites, each one of the chiefs and whites present have voluntarily signed their names to this instrument of writing.

"And it is further agreed that the Indians are not to be molested in their daily avocations by which they gain an honest living.

"And it is further agreed upon the part of the Indians that they are not to molest the property of the whites, nor to drive off or kill cattle that are running in the valley, and for both parties to live in peace and strive to promote amicably the general interests of both whites and Indians.

"Given under our hands at San Francis ranch this 31st day of January, 1862."

Signed for the Indians by Chief George, Chief Dick and Little Chief Dick, each of whom made his mark; for the whites by Samuel A. Bishop, L. J. Cralley, A. Van Fleet, S. E. Graves, W. A. Greenly, T. Everlett, John Welch, J. S. Howell, Daniel Wyman, A. Thomson and E. P. Robinson.

One of the chiefs missing from the conference was Joaquin Jim, leader of the tribe in southern Mono, which then included the valley as far south as Big Pine Creek. It was probably Joaquin Jim's braves who began renewed depredations. At any rate, the treaty proved to be merely a passing incident. Within two months war was on in earnest.

During February Jesse Summers came from Aurora for beef for that market. He gathered a few in the southern end of the valley and went back to Aurora, leaving Bart and Alney McGee to drive the band. They got as far as Big Pine Creek, where Jim's camp happened to be at the time. Jim and a few of his men visited the McGee camp, and acted so unfriendly that the brothers concluded to move. Alney went to get the horses, and Jim demanded something to eat. Bart poured him a cup of coffee, which he threw, cup and all, into the fire. McGee jumped toward the guns, which the Indians had set to one side. McGee took the precaution to discharge the weapons, then told Jim to take them and go, which he did. The brothers moved on and spent the night safely though uncomfortably in a wet meadow, with their horses close at hand. Alney went on the next day with Summers, whom he met at Van Fleet's. Bart went to the San Francis ranch. The next day he rode back to Putnam's and reported that the northern settlers wanted help. On his way down the speed of his horse got him safely past a band of Indians at Fish Springs, untouched by the many shots they fired at him.

Fifteen men came with McGee from Putnam's to help to move the cattle from Bishop Creek. The night they reached the San Francis ranch the Piutes provided a striking exhibition of fireworks, running about and waving burning pitchpine torches secured to long poles. The Indians surrounded the cabin and sent in a delegation. Though they claimed to be friendly, they held a war dance around the building, and told the whites that the Piutes had charmed lives and could spit out the bullets that might enter their bodies. The night passed without violence.

The next morning the drive of stock began, reaching what is now Keough's Hot Springs the first night. Though pickets were put out, Indians succeeded in driving off 200 or more head of cattle. The next morning three of the men went after the stock, and were met by a line of forty or fifty Indians who ordered them back — an order with which they could do nothing but comply. Indians hovered about the flanks of the drive down the valley, but did not molest it further.

A few days later Barton and John McGee, Taylor McGee, Allen Van Fleet, James Harness, Tom Hubbard, Tom Passmore, Pete Wilson and Charley Tyler ("Nigger Charley") were near Putnam's when they saw four Indians going toward the cattle. Bart and Taylor McGee, Van Fleet, Harness and Tyler went out to where they were. The Indians when interrogated said they were going after their horses. They were told they could go on, but must leave their weapons until they came back. This they refused to do. The controversy continued for some time. One account is that Van Fleet made the first threatening move by leveling his gun at an Indian ; his own story, and that of other whites, was that the Indian first pointed an arrow at him. Whatever the facts of this, Van Fleet turned his body and got the first wound, an arrow in his side, where its obsidian head remained until his death fifty years later. Harness was also wounded before the whites shot. In the melee which ensued all the Indians, one of whom was Chief Shondow, were slain. Hubbard was shot through the arm with an arrow.

It is fully possible that the whites were to blame in this affair. An account reaching Aurora held them responsible, and Barton McGee, in writing of it, said: "This occurrence created a little trouble in our ranks, some thinking we were not justified in firing on them and others saying we did exactly right. Be that as it may, it was done." This does not well accord with the narration of the fight as above printed on the statements of McGee and Van Fleet.

A few more than forty white men were gathered at Putnam's, and they began to strengthen their fortification. Rocks, old wagons, boxes and other materials were used to pile up a barricade. Charles Anderson was elected captain, and a constant guard was maintained while the company remained there. Sheriff Scott, of Mono, was among the men, and in a letter said : "The Indians appear warlike here, and we expect a battle before many days—possibly tonight. There are forty-two of us, armed with rifles, shotguns and six-shooters. We have fortified ourselves the best we could with wagons, oxbows, yokes, rawhides, etc. I can escape easily, but to do so would be to weaken the force in the fort, and so enable the redskins to wipe out those who would be obliged to remain."

A band of natives had gone to Van Fleet's cabin on the river, previous to this gathering at Putnam's, and had demanded admission. After some parley he gave them provisions. They set out toward Benton, then known as Hot Springs, where a prospector named E. S. Taylor lived alone. Taylor's cabin was attacked and riddled with bullets and he was killed, but not until ten of his assailants had paid with their lives. Van Fleet was the only authority for this statement, except that others wrote of passing and seeing the bullet-riddled building. A report taken to Aurora by Albert Jeffway, an express rider who had been in Owens Valley, told of the death of another Taylor, near Putnam's. Taylor, he said, was hotheaded, and got into a row during which he killed two or three Indians. The Piutes set fire to his cabin, and as he came from it they shot him. It is at least possible that this was a mistaken version of the Benton affair.

Two men known as Vance and Shorty were still in the upper end of the valley, or may have gone there from Putnam's, to gather up what stock they could. Seeing Indians after their animals, they went to investigate, were fired on, and killed two natives.

Whatever of division there may have been in the Putnam camp over the killing of Shondow, there was no dissent when it was proposed to strike a blow that would discourage raids on the cattle. Preparations for a campaign were made, and twenty-three men, led by Anderson, left Putnam's after dusk masked their movements. Cralley was chosen lieutenant. Scott Broder, the Me-Gees, Tyler, Harness and Shea were among those in the column, which went that night to the sod cabin of Ault and Sadler, not far from the Alabama hills

As soon as the east began to gray, three men were left with the horses at the cabin and the others set out in two equal squads. Anderson's detachment went to where the light of campfires could be seen over the Alabama hills ; the others went up the stream. The sun was just rising as Anderson came up to where the Indians were breakfasting. Firing commenced at once, a number of Indians being killed at the first volley. They ran to shelter in the rocks, "and a good shelter it was," wrote Bart McGee, "cavities where they were out of sight in less than thirty seconds. We could not follow them in, so we did the best we could from the outside, shooting into the mouths of their dens, while the Indians threw arrows among us in showers. It seemed the air was full of arrows all the time. They did not have any guns or they would have made it a hard fight for us. We fought there for about an hour before the other boys, hearing our firing and coming across the rough hill, could reach us. We fought until about 1 o'clock, hitting some 30 or 40 of them, destroying about a ton of dried meat and some of their camp outfits." The white casualties included another arrow hole in Hubbard's arm, a wound in Harness' forehead made by an arrow which shattered against the skull without penetrating, and an arrow wound in Scott Broder's shoulder. The last mentioned injury was so troublesome that the citizens withdrew to the fort, leaving the natives in their stronghold. While McGee mentions that 30 or 40 Indians were hit, and another account said that Negro Charley Tyler himself shot four Indians, a report sent to Los Angeles gave the total Indian strength in the fight as 40 and said that their dead numbered eleven.

Bryant- Admin

- Posts : 1452

Join date : 2012-01-28

Age : 35

Location : John Day, Oregon

Re: Owens Valley Indain Wars

Re: Owens Valley Indain Wars

WHITES DEFEATED AT BISHOP CREEK

During this time the Owens Valley Indians had sent calls for aid to all their people. Nevada Piutes had suffered severely in a recent war of their own, and the majority were not inclined to hunt further trouble. They had realized the truth of predictions attributed to Numaga, one of their leaders. While it is a digression from the immediate subject, the speech credited to Numaga in trying to keep his braves from the warpath is worth preserving:

"You would make war upon the whites. I ask you to pause and reflect. The white men are like the stars over your heads. You have wrongs, great wrongs, that rise up like these mountains before you; but can you from the mountain tops reach up and blot out those stars? Your enemies are like the sands in the beds of your rivers: when taken away they only give place for more to come and settle here. Could you defeat the whites, from over the mountains in California would come to help them an army of white men that would cover your country like a blanket. What hope is there for the Pinto/ From where is to come your guns, your powder, your lead, your dried meats to live upon, and hay to feed your ponies while you carry on this war? Your enemies have all these things, more than they can use. They will come like the sand in a whirlwind, and drive you from your homes. You will be forced among the barren rocks of the north, where your ponies will die, where you will see the women and old men starve, and listen to the cries of your children for food. I love my people; let them live; and when their spirits shall be called to the great camp in the southern sky, let their bones rest where their fathers were buried."

But in spite of advice, some came from the Nevada tribes to venture further in warfare. More came from the west, across the Sierras, from the Kern and Tulare bands that had been but recently defeated, and from southern California. Some, like Joaquin Jim who was already an Owens Valley leader, had been outlawed by their own people. Jim was a Fresno renegade, a man of unusual courage and determination, and he was never reconciled to white rule. The gathered Indian host in Owens Valley was estimated at from 1,500 to 2,000 fighting men.

The Reds found allies in the mining camp of Aurora, in the persons of two merchants named Wingate and Cohn, who were said to have carried on a thriving traffic in supplying ammunition for what guns the western Nevada and Mono Indians had. The same Wingate refused to sell ammunition to a messenger from the settlers, saying that all the whites in Owens Valley should be killed.

Al Thompson and a companion were sent to Aurora for help for the threatened settlers. A party of eighteen was organized there, commanded by Capt. John J. Kellogg, a former army officer. One of its members was Alney L. McGee, who had gone to Aurora from the valley.

After the Lone Pine battle the citizens at Putnam's had elected Mayfield their captain. Accounts of the expedition next starting from there do not agree, ranging from twenty-two to thirty-five ; the best supported estimate seems to be thirty-three. This force moved northerly to attack the Indians. At Big Pine they found the bodies of R. Hanson and Tallman (or Townsend), who had been killed by the Indians a few days before. Both corpses had been torn and mutilated by coyotes, and that of Hanson (a brother of A. C. Hanson, one of the expedition and in later years County Judge) was identified by the teeth.

Kellogg came clown east of the river, the same day. He believed the Mayfield command, which could be seen across the valley, to be hostiles. The mistake was straightened out and the two commands united. All night long the hostiles occupied the rock-strewn hillsides near by, and kept up a continuous howling. The next day, as the force moved northward, an Indian scout was killed by Tex Berry. Dr. A. H. Mitchell, who proved to be an abject coward in the later fight, acted consistently with that character by scalping the Indian and tying the bloody trophy to his saddle. He afterward lost horse, saddle and all. About noon of April 6th camp was made at a ditch or ravine about two miles southwest of the present town of Bishop.

The Indians held a line extending from a small black butte in the valley across Bishop Creek and to the foothills south. Their numbers were variously estimated at from 500 to 1,500. Opposing them was a white force of from fifty to sixty-three men.

The Piutes were defiant in their demonstrations, and the white men waited only long enough to eat a meal before going into action. Kellogg's force moved up along the creek; Mayfield took his men more southerly. A deep wash was encountered, and the pack animals were left there with a man in charge. Mayfield, Morrison and Van Fleet were at the head of the line when the Indians opened fire. Van Fleet dismounted and handed his bridle to Mayfield. A bullet penetrated Morrison's body, and Mayfield, not seeing his men coming up, became panic-stricken and would have fled leaving Van Fleet afoot if he had not been threatened with summary vengeance.

Kellogg saw that the Indians were about to move around and either cut off the line of retreat or separate the two parties of whites. In response to his call for a volunteer to warn Mayfield, Alney McGee made the ride, during which his horse was killed.

The white men then retreated to the shelter of the ditch. Morrison was put in front of Bart McGee, on the latter's horse, and with Alney McGee steadying him was taken to the trench. "Cage," or James Pleasant, a dairyman who had come from Visalia, was in front of them. They happened to be looking directly at him when a bullet hole appeared in the light gum coat he wore. He did not reply to a question asked, but rose in his stirrups and fell from his horse, dead. The situation was so pressing that for the time the body was left where it fell.

Anderson collected some of the men at a small hill and kept the foe back until Morrison could be taken to a safer place. As the men went back, an Indian wearing only some feathers in his hair was seen going toward the pack train. It was suggested to Hanson that there was his chance to get revenge for his brother's death, and Hanson and Tyler rode out and killed the too venturesome red man. The latter's costume was similar to what a great many of the warriors were wearing at the time. "The uniforms they wore was nawthin' much before, an' rawther less than 'arf o' that be'ind."

The whites reached the ditch intrenchment without further casualties, and from there maintained a defensive battle. One veteran of the fight stated that "Stock" Robinson killed an Indian who was crawling through the ditch to get at close quarters with the defenders. One Indian had a point of vantage behind a pile of grass from which he fired several shots. He was killed by Van Fleet, who watched for his rising to shoot. Mitchell, who had distinguished himself by scalping the Indian scout killed on the way up the valley, proposed that all make a run for safety. Anderson, knowing that if that were done the whole party would be exterminated, said he would shoot the first man who left them to run. Mitchell then bravely proclaimed his own intention of taking a shot at any one who would exhibit such miserable cowardice.

The whites had spread out some of their powder to have it handy for loading purposes. Some one struck a match which fell into it, and one man was severely burned in the explosion which followed.

Darkness came on, and firing from the Indian lines almost ceased. N. F. Scott, Sheriff of Mono, who had come from Putnam's with the Mayfield party, raised his head above the ditch rim as he undertook to light his pipe. As he did an Indian bullet struck him in the temple, causing instant death. He had come into the valley on official business a short time before.

The beleaguered whites waited until the moon went down, well along in the night, before making a move. Then they retreated to Big Pine, unmolested. Morrison was taken with them, but died soon after reaching Big Pine Creek. This brought the white dead up to three. The number of Indians who fell was unknown, but was variously estimated at from five to fifteen or more. A report published soon afterward said that eleven Indians were killed. The fatalities in this affair, as in nearly every case during the fighting, resulted from bullet wounds. Indian arrows did little harm except at close quarters. Fortunately for their opponents the Indians had but few guns, and were too ignorant of their care and use to make them very effective. Had Piutes possessed any marked degree of courage they could have wiped out the little company of white men, though of course it would have been at a heavy cost to themselves.

The men, who were in this fight, so far as ascertained from different records, included Harrison Morrison, "Cage" Pleasant and N. F. Scott, who were killed ; Captain Mayfield, Charles Anderson, Alney McGee, Barton McGee, A. Van Fleet, A. C. Hanson, Thos. G. Beasley, R. E. Phelps, E. P. Robinson, John Welch, Thomas Hubbard, Thomas Passmore, William L. Moore, A. Graves, James Harness, John Shea, —. Boland, Pete Wilson, L. F. Cralley, Tex Berry, James Palmer, A. H. Mitchell, "Negro" Charley Tyler, a Tejon Indian, and others unrecorded.

No two of the several accounts of this fight agree in all respects ; the versions having the most corroboration of fact or probability have been accepted.

During this time the Owens Valley Indians had sent calls for aid to all their people. Nevada Piutes had suffered severely in a recent war of their own, and the majority were not inclined to hunt further trouble. They had realized the truth of predictions attributed to Numaga, one of their leaders. While it is a digression from the immediate subject, the speech credited to Numaga in trying to keep his braves from the warpath is worth preserving:

"You would make war upon the whites. I ask you to pause and reflect. The white men are like the stars over your heads. You have wrongs, great wrongs, that rise up like these mountains before you; but can you from the mountain tops reach up and blot out those stars? Your enemies are like the sands in the beds of your rivers: when taken away they only give place for more to come and settle here. Could you defeat the whites, from over the mountains in California would come to help them an army of white men that would cover your country like a blanket. What hope is there for the Pinto/ From where is to come your guns, your powder, your lead, your dried meats to live upon, and hay to feed your ponies while you carry on this war? Your enemies have all these things, more than they can use. They will come like the sand in a whirlwind, and drive you from your homes. You will be forced among the barren rocks of the north, where your ponies will die, where you will see the women and old men starve, and listen to the cries of your children for food. I love my people; let them live; and when their spirits shall be called to the great camp in the southern sky, let their bones rest where their fathers were buried."

But in spite of advice, some came from the Nevada tribes to venture further in warfare. More came from the west, across the Sierras, from the Kern and Tulare bands that had been but recently defeated, and from southern California. Some, like Joaquin Jim who was already an Owens Valley leader, had been outlawed by their own people. Jim was a Fresno renegade, a man of unusual courage and determination, and he was never reconciled to white rule. The gathered Indian host in Owens Valley was estimated at from 1,500 to 2,000 fighting men.

The Reds found allies in the mining camp of Aurora, in the persons of two merchants named Wingate and Cohn, who were said to have carried on a thriving traffic in supplying ammunition for what guns the western Nevada and Mono Indians had. The same Wingate refused to sell ammunition to a messenger from the settlers, saying that all the whites in Owens Valley should be killed.

Al Thompson and a companion were sent to Aurora for help for the threatened settlers. A party of eighteen was organized there, commanded by Capt. John J. Kellogg, a former army officer. One of its members was Alney L. McGee, who had gone to Aurora from the valley.

After the Lone Pine battle the citizens at Putnam's had elected Mayfield their captain. Accounts of the expedition next starting from there do not agree, ranging from twenty-two to thirty-five ; the best supported estimate seems to be thirty-three. This force moved northerly to attack the Indians. At Big Pine they found the bodies of R. Hanson and Tallman (or Townsend), who had been killed by the Indians a few days before. Both corpses had been torn and mutilated by coyotes, and that of Hanson (a brother of A. C. Hanson, one of the expedition and in later years County Judge) was identified by the teeth.

Kellogg came clown east of the river, the same day. He believed the Mayfield command, which could be seen across the valley, to be hostiles. The mistake was straightened out and the two commands united. All night long the hostiles occupied the rock-strewn hillsides near by, and kept up a continuous howling. The next day, as the force moved northward, an Indian scout was killed by Tex Berry. Dr. A. H. Mitchell, who proved to be an abject coward in the later fight, acted consistently with that character by scalping the Indian and tying the bloody trophy to his saddle. He afterward lost horse, saddle and all. About noon of April 6th camp was made at a ditch or ravine about two miles southwest of the present town of Bishop.

The Indians held a line extending from a small black butte in the valley across Bishop Creek and to the foothills south. Their numbers were variously estimated at from 500 to 1,500. Opposing them was a white force of from fifty to sixty-three men.

The Piutes were defiant in their demonstrations, and the white men waited only long enough to eat a meal before going into action. Kellogg's force moved up along the creek; Mayfield took his men more southerly. A deep wash was encountered, and the pack animals were left there with a man in charge. Mayfield, Morrison and Van Fleet were at the head of the line when the Indians opened fire. Van Fleet dismounted and handed his bridle to Mayfield. A bullet penetrated Morrison's body, and Mayfield, not seeing his men coming up, became panic-stricken and would have fled leaving Van Fleet afoot if he had not been threatened with summary vengeance.

Kellogg saw that the Indians were about to move around and either cut off the line of retreat or separate the two parties of whites. In response to his call for a volunteer to warn Mayfield, Alney McGee made the ride, during which his horse was killed.

The white men then retreated to the shelter of the ditch. Morrison was put in front of Bart McGee, on the latter's horse, and with Alney McGee steadying him was taken to the trench. "Cage," or James Pleasant, a dairyman who had come from Visalia, was in front of them. They happened to be looking directly at him when a bullet hole appeared in the light gum coat he wore. He did not reply to a question asked, but rose in his stirrups and fell from his horse, dead. The situation was so pressing that for the time the body was left where it fell.

Anderson collected some of the men at a small hill and kept the foe back until Morrison could be taken to a safer place. As the men went back, an Indian wearing only some feathers in his hair was seen going toward the pack train. It was suggested to Hanson that there was his chance to get revenge for his brother's death, and Hanson and Tyler rode out and killed the too venturesome red man. The latter's costume was similar to what a great many of the warriors were wearing at the time. "The uniforms they wore was nawthin' much before, an' rawther less than 'arf o' that be'ind."

The whites reached the ditch intrenchment without further casualties, and from there maintained a defensive battle. One veteran of the fight stated that "Stock" Robinson killed an Indian who was crawling through the ditch to get at close quarters with the defenders. One Indian had a point of vantage behind a pile of grass from which he fired several shots. He was killed by Van Fleet, who watched for his rising to shoot. Mitchell, who had distinguished himself by scalping the Indian scout killed on the way up the valley, proposed that all make a run for safety. Anderson, knowing that if that were done the whole party would be exterminated, said he would shoot the first man who left them to run. Mitchell then bravely proclaimed his own intention of taking a shot at any one who would exhibit such miserable cowardice.

The whites had spread out some of their powder to have it handy for loading purposes. Some one struck a match which fell into it, and one man was severely burned in the explosion which followed.

Darkness came on, and firing from the Indian lines almost ceased. N. F. Scott, Sheriff of Mono, who had come from Putnam's with the Mayfield party, raised his head above the ditch rim as he undertook to light his pipe. As he did an Indian bullet struck him in the temple, causing instant death. He had come into the valley on official business a short time before.

The beleaguered whites waited until the moon went down, well along in the night, before making a move. Then they retreated to Big Pine, unmolested. Morrison was taken with them, but died soon after reaching Big Pine Creek. This brought the white dead up to three. The number of Indians who fell was unknown, but was variously estimated at from five to fifteen or more. A report published soon afterward said that eleven Indians were killed. The fatalities in this affair, as in nearly every case during the fighting, resulted from bullet wounds. Indian arrows did little harm except at close quarters. Fortunately for their opponents the Indians had but few guns, and were too ignorant of their care and use to make them very effective. Had Piutes possessed any marked degree of courage they could have wiped out the little company of white men, though of course it would have been at a heavy cost to themselves.

The men, who were in this fight, so far as ascertained from different records, included Harrison Morrison, "Cage" Pleasant and N. F. Scott, who were killed ; Captain Mayfield, Charles Anderson, Alney McGee, Barton McGee, A. Van Fleet, A. C. Hanson, Thos. G. Beasley, R. E. Phelps, E. P. Robinson, John Welch, Thomas Hubbard, Thomas Passmore, William L. Moore, A. Graves, James Harness, John Shea, —. Boland, Pete Wilson, L. F. Cralley, Tex Berry, James Palmer, A. H. Mitchell, "Negro" Charley Tyler, a Tejon Indian, and others unrecorded.

No two of the several accounts of this fight agree in all respects ; the versions having the most corroboration of fact or probability have been accepted.

Bryant- Admin

- Posts : 1452

Join date : 2012-01-28

Age : 35

Location : John Day, Oregon

Re: Owens Valley Indain Wars

Re: Owens Valley Indain Wars

WHITES AGAIN BEATEN

Enters now into these chronicles the nation's soldiery, also one Warren Wasson, acting Indian Agent for the Territory of Nevada.

Through news reaching Carson by way of Aurora, Wasson learned of the beginning of trouble in Owens Valley. Under date of March 25, 1862, he telegraphed to James W. Nye, Governor of Nevada, who was then in San Francisco.

"Indian difficulties on Owens River confirmed. Hostiles advancing this way. I desire to go and if possible prevent the war from reaching this territory. If a few men poorly armed go against those Indians defeat will follow and a long and bloody war will ensue. If the whites on Owens River had prompt and adequate assistance it could be checked there. I have just returned from Walker River. Piutes alarmed. I await reply."

Governor Nye promptly conferred with General Wright, commanding the Department of the Pacific, and on the same day notified Wasson to the following effect:

"General Wright will order 50 men to go with you to the scene of action. You may take 50 of my muskets at the fort, and some ammunition with you, and bring them back. Confer with Captain Rowe."

It will be observed that the Governor was careful of the property under his charge. Presumably the guns were for the arming of settlers in the valley.

Captain E. A. Rowe, of Company A, Second California Cavalry, was ranking officer and commander at Fort Churchill, Nevada. Wasson immediately visited him, and the result was an order to Lieutenant Herman Noble to take fifty men to "Aurora and vicinity." "You will be governed by circumstances, in a great measure," his instructions read, "but upon all occasions it is desirable that you consult the Indian Agent, Mr. W. Wasson, who accompanies the expedition for the purpose of restraining the Indians from hostilities. Upon no consideration will you allow your men to engage the Indians without his sanction."

Wasson came on ahead of the troops. He found the Walker River Indians greatly excited, and apprehensive of general war with the whites. He sent messengers to the different bands of Piutes in that region, with instructions to keep quiet until his return. The mass of the natives were anxious to keep out of trouble, and he found all quiet when he went back.

A Piute named Robert accompanied him to Mono Lake, where the Indians were congregated and preparing for a war they feared. They were much pleased with his mission, and sent with him one of their number who could speak the Owens River Piute dialect.

Wasson and his interpreters joined Noble'scolumn at Adobe Meadows on the night of April 4th. The next day he traveled eight or ten miles ahead of the soldiers, and about noon passed the boundary of the Owens River Piute territory. On the night of the 6th camp was made at the northerly crossing of Owens River. At that very hour the Mayfield and Kellogg companies were defending themselves in the trench near Bishop Creek. Wasson saw no Indians, but plenty of fresh signs. On the following morning the Mono Indian said that he knew the Indians were to the right and up the valley. He was sent to interview them, with a message that the purpose of the mission was to inquire into the cause of the difficulties and to arrange a fair settlement.

Wasson and the Walker River Indian went on south. After going twelve miles down the river they saw a body of men at the foot of the Sierras and waited until Noble came up. Lieutenant Noble and Wasson then left the cavalry and went across the valley to learn who the men were. They found the citizens who had retreated from Bishop Creek, together with troopers of the Second California Cavalry under Lieutenant Colonel George S. Evans. Evans had left Los Angeles March 19th, and shortened the trip to Owens Valley by keeping to the east of the Sierras instead of going into the San Joaquin Valley and crossing Walker's Pass, as seems to have been the invariable route before then. This appears to have been the first travel on the route now used south of Walker's Pass. He arrived at Owens Lake April 2d. He found a dozen men and a few women and children at Putnam's "fort." Leaving Captain Winne and seven soldiers there, Evans moved on up the valley with seventy-three men and met the Mayfield-Kellogg men near Big Pine.

Wasson made his mission known, but found little encouragement for peaceful hopes. The larger force wished only to exterminate the hostiles. When Mayfield met the cavalry, Evans had induced forty-five of the citizens to turn back northward with his company, the rest being sent on to Putnam's.

The meeting with the contingent from Nevada occurred about six miles south of Bishop Creek. Evans, being the ranking officer, directed Noble to bring up his company. When this was done the force moved to and camped at the scene of the previous day's fighting. The body of Pleasant, left in the flight of the citizens, was found, shockingly mutilated. All his clothing had been taken for Indian use. The body, wrapped in a blanket, was buried. It may be noted that when circumstances favored the Piutes again dug up the remains and took therefrom the blanket shrouding them. Once more the whites made a grave for Pleasant, at a point a little east of the San Francis ranch. Search in later years failed to discover the place of its final interment. Pleasant Valley, a small subdivision of Owens Valley, was named for this victim of the war. The body of Scott, buried in the trench the night of the retreat, was undisturbed.

Evans started scouting parties in different directions at daylight of the 8th. Eight or ten men who had gone northwesterly returned about noon and reported having found the enemy in force twelve miles to the northwest, in what is now called Round Valley. A rapid movement in that direction was ordered, and in two hours the soldiers and citizens reached the mouth of the canyon in which the Indians were believed to be. A heavy snowstorm had begun there, and a strong gale swept down from the summits. Evans ordered an advance, sending Lieutenants Noble and Oliver up one ridge with forty men while he and Lieutenant French, with an equal number, took the opposite wall of the canyon. Wasson criticizes the wisdom of this plan, as the gale, all in favor of the Indians, would have given them a strong advantage. The pursued foes had gone on, however, and no Indians were found. The troops returned to the valley below.